Abstract:

This paper examines the paradoxical relationship between globalisation and inequality in the Global South. While globalisation has stimulated trade, investment, and technological flows, it has also deepened socio-economic inequalities between and within states. By analysing case studies from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the paper highlights how structural adjustment programmes, dependency on commodity exports, and global financial imbalances have reinforced asymmetrical power relations. The article concludes that without addressing governance deficits, redistributive justice, and fairer integration into the global economy, globalisation risks perpetuating cycles of poverty and marginalisation in the Global South.

Globalisation has often been presented as an engine of progress, promising greater interconnectedness, trade liberalisation, technological transfer, and development opportunities. However, for much of the Global South, the experience of globalisation has been ambivalent. While some countries have benefitted from increased foreign direct investment (FDI), access to international markets, and knowledge flows, others have faced widening economic inequality, social dislocation, and political instability. This paper examines how globalisation has exacerbated inequality in the Global South, exploring its effects on economic structures, labour markets, governance, and social outcomes. It argues that although globalisation creates opportunities, the distribution of its benefits is highly uneven, reinforcing pre-existing inequalities within and between states.

Globalisation and the Promise of Development

In the 1990s, the dominant discourse of international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) framed globalisation as a path to development. Through structural adjustment programmes, liberalisation of trade, and privatisation, Global South economies were expected to integrate into global markets and achieve sustainable growth (Stiglitz, 2002).

Indeed, some countries experienced economic gains. For example, Vietnam’s integration into global supply chains significantly reduced poverty, with poverty rates declining from over 70% in the late 1980s to less than 6% by 2020 (World Bank, 2021). Similarly, countries like India and China have harnessed globalisation to foster industrialisation and rapid GDP growth (Rodrik, 2011).

However, these success stories are unevenly spread. Many African, Latin American, and South Asian states remain on the margins of the global economy, exporting raw materials while importing high-value goods. This structural dependence perpetuates unequal terms of trade and vulnerability to global market shocks (Amin, 1976).

Economic Inequality: Winners and Losers

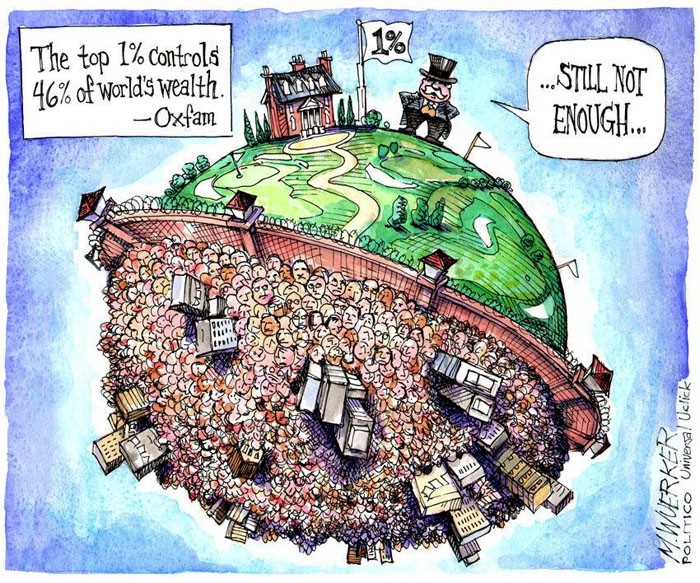

Globalisation has produced a paradox in the Global South: while national GDP levels may rise, income inequality often increases within countries.

The integration of economies into global value chains has benefitted urban elites and multinational corporations but left rural populations and informal workers behind. For example, in Nigeria, oil exports generate billions of dollars annually, yet over 40% of the population lives below the poverty line (UNDP, 2020). Similarly, Latin America remains one of the most unequal regions in the world, despite decades of integration into global markets (ECLAC, 2019).

The “Kuznets curve” hypothesis—that inequality would first rise and then fall as economies develop—has not held true for many Global South states. Instead, inequality has persisted or worsened, with limited redistribution mechanisms in place (Piketty, 2014).

Moreover, the digital divide further entrenches inequality. Access to technology, internet connectivity, and education is concentrated among the middle classes and elites in urban centres, while rural populations remain excluded from digital economies (OECD, 2019).

Labour Markets and Precarity

One of the most visible effects of globalisation in the Global South is the transformation of labour markets.

On the one hand, globalisation has created jobs through outsourcing and foreign investment. For instance, the rise of call centres in India or textile manufacturing in Bangladesh demonstrates how low-cost labour can attract global capital (Kabeer, 2004).

On the other hand, these jobs are often precarious, poorly paid, and exploitative. The Rana Plaza collapse in 2013, which killed over 1,100 Bangladeshi garment workers, revealed the human costs of global supply chains driven by multinational corporations seeking cheap labour (Reinecke & Donaghey, 2015).

The informal sector has also expanded, with millions of workers lacking contracts, social protection, or labour rights. In Sub-Saharan Africa, over 85% of employment is informal, leaving workers vulnerable to global economic fluctuations (ILO, 2018).

Governance, Dependency, and Global Power Structures

Globalisation is not only an economic process but also a political one. The integration of Global South economies into global markets has often reinforced dependency on external powers and international financial institutions.

Structural adjustment programmes imposed by the IMF and World Bank in the 1980s and 1990s led to cuts in social spending, privatisation of state-owned enterprises, and deregulation. While intended to stabilise economies, these reforms frequently deepened poverty and inequality (Stiglitz, 2002).

Furthermore, trade agreements and investment treaties often favour Global North states and multinational corporations. For example, African countries exporting raw cocoa receive a fraction of the value compared to European firms processing chocolate, illustrating the persistence of unequal economic relationships (UNECA, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed these inequalities. While wealthy countries secured vaccines through advanced purchase agreements, many Global South nations faced shortages, demonstrating the asymmetrical power dynamics in global health governance (UNCTAD, 2021).

Social Inequality: Gender, Education, and Migration

Globalisation has also had profound social consequences, shaping inequality along gender, educational, and migratory lines.

- Gender Inequality: Women in the Global South are disproportionately concentrated in low-paid export industries such as textiles, agriculture, and domestic work. While globalisation has created employment opportunities, it has often reinforced gendered labour hierarchies (Elson, 1999).

- Education: Access to education is increasingly tied to globalisation. Skilled workers benefit from higher wages in knowledge-based industries, while unskilled workers face marginalisation. This education gap perpetuates inequality across generations (Sen, 1999).

- Migration: Globalisation has intensified migration flows, both voluntary and forced. While remittances provide income to households in the Global South, brain drain deprives many countries of skilled professionals, widening development gaps (Castles, 2010).

Resistance and Alternatives

Despite these challenges, the Global South has not been a passive recipient of globalisation but has developed forms of resistance and alternative models.

- Regional integration efforts such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) aim to reduce dependency on external markets and strengthen intra-African trade (UNECA, 2020).

- South-South cooperation has emerged as a counterbalance to North-South dependency, with countries like China, India, and Brazil investing in infrastructure, technology, and health across Africa and Latin America (Alden & Vieira, 2005).

- Civil society movements have mobilised against exploitative practices, demanding fair trade, labour rights, and environmental protections.

These efforts highlight that globalisation is not a one-way process imposed from above, but a contested terrain where different actors seek to reshape outcomes.

Conclusion

Globalisation has been a double-edged sword for the Global South. While it has brought opportunities for trade, investment, and knowledge transfer, it has also exacerbated inequality, entrenched dependency, and deepened social divides. The challenge lies in creating a form of globalisation that is inclusive, equitable, and sustainable.

This requires policies that strengthen local governance, regulate multinational corporations, invest in education and technology, and ensure fair terms of trade. Without such reforms, globalisation will continue to reproduce patterns of inequality, leaving large parts of the Global South marginalised in the global economy.

References

- Alden, C. & Vieira, M.A. (2005) ‘The new diplomacy of the South: South Africa, Brazil, India and trilateralism’, Third World Quarterly, 26(7), pp. 1077–1095.

- Amin, S. (1976) Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Castles, S. (2010) ‘Understanding global migration: A social transformation perspective’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(10), pp. 1565–1586.

- ECLAC (2019) Social Panorama of Latin America 2019. Santiago: United Nations.

- Elson, D. (1999) ‘Labour markets as gendered institutions: Equality, efficiency and empowerment issues’, World Development, 27(3), pp. 611–627.

- ILO (2018) Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture. 3rd edn. Geneva: ILO.

- Kabeer, N. (2004) Globalization, Labor Standards and Women’s Rights: Dilemmas of Collective (In)action in an Interdependent World. Feminist Economics, 10(1), pp. 3–35.

- OECD (2019) Bridging the Digital Divide. Paris: OECD.

- Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Reinecke, J. & Donaghey, J. (2015) ‘After Rana Plaza: Building coalitional power for labour rights between unions and (consumption-based) social movement organisations’, Organization, 22(5), pp. 720–740.

- Rodrik, D. (2011) The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Sen, A. (1999) Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stiglitz, J. (2002) Globalization and Its Discontents. London: Penguin.

- UNCTAD (2021) Trade and Development Report 2021. Geneva: UNCTAD.

- UNECA (2020) Assessing Regional Integration in Africa IX: Next Steps for the African Continental Free Trade Area. Addis Ababa: UNECA.

- UNDP (2020) Nigeria Human Development Report 2020. New York: UNDP.

- World Bank (2021) Vietnam Poverty Assessment 2021. Washington DC: World Bank.

Leave a comment