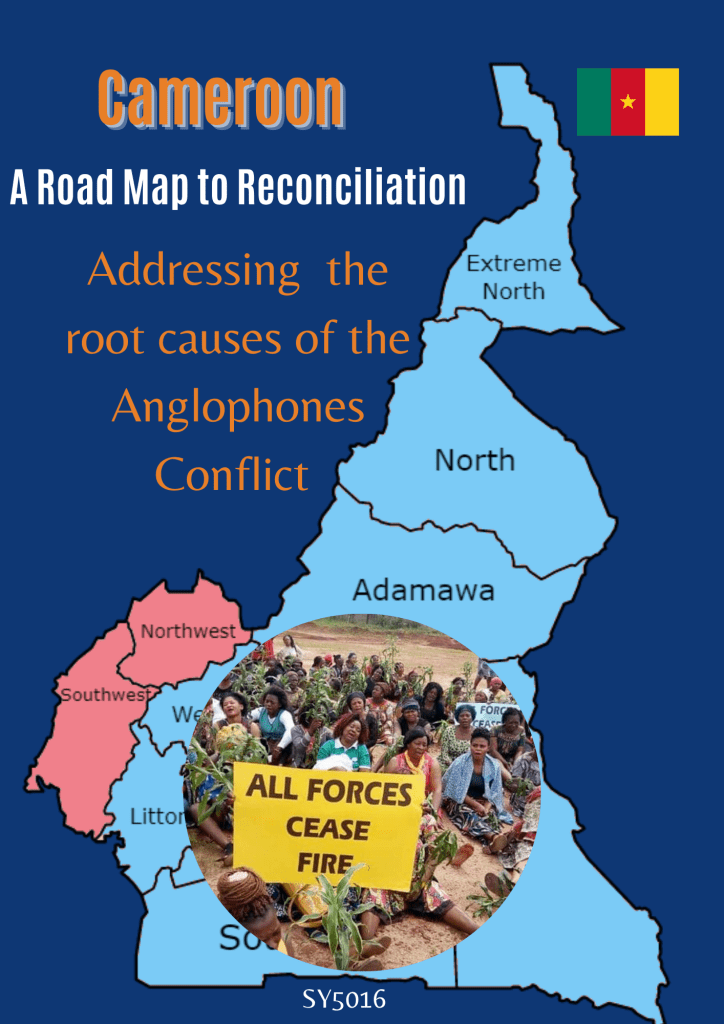

The current conflict in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon has evolved into a multifaceted crisis, presenting significant challenges to regional stability, human rights, and international peace efforts. This Policy Paper aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the conflict, tracing its roots from historical grievances to the current humanitarian crisis. The importance of this issue extends beyond Cameroon’s borders, influencing the broader Central African region and implicating international legal and humanitarian norms. Cameroon’s colonial history, characterised by German, British, and French rule, has left an enduring legacy on its socio-political landscape. The division of Cameroon into Francophone and Anglophone regions, a direct result of colonial rule, has fostered deep-seated cultural and linguistic divides. Awasom (2000) argues that the amalgamation of these distinct regions under a single state post-independence was fraught with challenges, exacerbating regional disparities and discontent. Similarly, Nugent (2004) provides a broader context on how colonial legacies have shaped post-colonial state formation and conflicts in Africa, with a particular focus on the arbitrary drawing of colonial borders and its impacts on ethnic and linguistic groups. The evolution of this crisis, from historical grievances to the present conflict, has been marked by a series of political, economic, and social failures. Konings and Nyamnjoh (2005) delve into the complexities of this issue, highlighting how perceived marginalisation and inequities have fuelled the discontent leading to the current state of unrest. This Paper also examines Cameroon’s obligations under international treaties and conventions, particularly in relation to human rights and the protection of civilians in conflict zones. The analysis draws on a range of scholarly works and reports to provide a comprehensive understanding of the situation. In addressing this crisis, it is crucial to consider the historical, socio-political, and legal dimensions that have shaped the conflict. Finally, This Paper aims to offer actionable recommendations to the international community to address the immediate humanitarian needs and work towards a long-term resolution of the conflict.

Historical Context and Colonial Legacy

The conflict in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon cannot be fully understood without delving into its colonial past and the impact of the post-colonial political landscape. The territory now known as Cameroon was once a German colony, later divided between Britain and France after World War I. This partition laid the groundwork for the linguistic and cultural divide that characterises the nation today. Post World War II, a wave of decolonisation swept across Africa. The colonial borders, arbitrarily drawn by these colonial powers, have had a lasting impact on post-colonial Africa. Herbst (1989), highlights how these borders, often cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, have contributed to conflict and instability in many African nations, including Cameroon. A similar argument is presented by Nugent (2004) emphasising how the legacy of colonialism continues to shape political and social dynamics in African countries. The lack of consideration for ethnic and cultural realities in the drawing of these borders has been particularly detrimental. As Mbembe (2001) argues, the imposition of these borders has often led to a “politics of belonging,” where the struggle over resources, power, and identity gets entangled with territorial claims, exacerbating conflicts like the one in Cameroon. In this context, British-administered Southern Cameroons and French Cameroun moved towards independence in 1960. The 1961 plebiscite, a critical juncture in Cameroon’s history, led to the unification of the Anglophone and Francophone regions, forming a federal state. This agreement promised equal status and autonomy to both regions. However, as Joseph (1977) points out, the promise of a federal structure was not fully realised, leading to increasing discontent among the Anglophone population. The Cameroon government, primarily Francophone-dominated, gradually eroded the federal system, undermining the autonomy and rights of the Anglophone region. The centralisation policies, particularly under President Ahidjo and his successor Paul Biya who succeeded in 1982, significantly marginalised the Anglophone community. Fombad (2001) rightly argues that these policies were instrumental in deepening the divide and fostering a sense of alienation among Anglophones. The roles played by historical leaders, both Anglophone and Francophone, during this period were pivotal. As elucidated by Fanso (1995) Anglophone leaders like John Ngu Foncha and Solomon Tandeng Muna initially advocated for the federal system but later faced criticism for their inability to effectively safeguard Anglophone interests.

Evolution of the Conflict

The conflict has evolved over several decades, transforming from a political disagreement to a full-blown humanitarian crisis. This evolution can be segmented into distinct phases, each marked by key events and turning points. Initially, the grievances of the Anglophone community were primarily political, stemming from the perceived marginalisation in the governance of the newly unified state. As elucidated in the works of Joseph (1977) and Fombad (2001), the gradual erosion of the federal structure promised in 1961 led to increasing disillusionment. During this period, the grievances were largely expressed through political activism and calls for reform. Key figures like John Ngu Foncha and Solomon Tandeng Muna were at the forefront, advocating for the rights of the Anglophone population within the framework of a united Cameroon. The 1990s saw the rise of a more vocal and organised Anglophone civil society. Groups like the Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) and the Cameroon Anglophone Movement (CAM) emerged, advocating for greater autonomy or outright secession. Konings and Nyamnjoh (2005) note that this period was marked by a shift from seeking reform within the system to challenging the legitimacy of the state structure. The situation took a dramatic turn in the mid-2010s. The government’s heavy-handed response to peaceful protests in 2016 and 2017, involving lawyers and teachers who were protesting against the imposition of French laws and education in Anglophone regions, marked a significant escalation. As covered by Human Rights Watch, the government’s use of force and subsequent crackdown on dissenters pushed some factions of the Anglophone movement towards armed resistance. The conflict has since gained international attention, with various reports and analyses being published on the human rights situation. The International Crisis Group, for instance, has highlighted the increasing brutality of the conflict and the dire humanitarian situation resulting from it. The UN and other international bodies have expressed concern over the violence and the growing number of internally displaced persons and refugees.

Current Situation

As of now, the conflict has become deeply entrenched, with separatist groups engaging in armed struggle against government forces. The government’s militarised approach to the crisis has led to widespread allegations of human rights abuses. The situation remains volatile, characterised by significant loss of life, widespread displacement, and a growing number of refugees seeking asylum in neighbouring countries, particularly Nigeria. The exact number of victims is challenging to ascertain due to the ongoing nature of the conflict and limited access to some areas. However, reports from human rights organisations indicate a high number of civilian casualties. According to Human Rights Watch (2019), there have been numerous instances of unlawful killings and violence perpetrated by both government forces and armed separatists. Amnesty International (2020) has also reported on extrajudicial killings, abductions, and torture in the region, highlighting the severe impact of the conflict on the civilian population. The number of IDPs has continued to grow since the escalation of the conflict. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) reported in 2020 that Cameroon was among the countries with the highest levels of new displacement related to conflict and violence. As per the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) report (2020), there are hundreds of thousands of IDPs in the Northwest and Southwest regions, with many living in precarious conditions without adequate access to basic necessities. The crisis has forced many Cameroonians to flee to Nigeria. The UNHCR has been actively involved in providing assistance to these refugees. As of 2020, the UNHCR reported that over 60,000 Cameroonian refugees had been registered in Nigeria, with many residing in refugee settlements and host communities in the states bordering Cameroon. The United Nations, through its various agencies, has been involved in providing humanitarian aid, monitoring the human rights situation, and advocating for a peaceful resolution to the conflict. The United Nations Security Council (UNSC), while not yet formally intervening in the conflict, has been briefed on the situation, as noted in reports by the Secretary-General on the Central African region. The UN Special Representative for Central Africa and the Head of UNOCA have been involved in diplomatic efforts to encourage dialogue between the conflicting parties, as detailed in UNOCA’s reports.

Cameroon’s Obligations under International Treaties and Conventions

Cameroon, as a member of the international community, is bound by various international treaties and conventions. These obligations play a crucial role in shaping the country’s legal and ethical responsibilities, especially in the context of the Anglophone conflict. Cameroon is a signatory to several key international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). As Donnelly (2013) elaborates, these treaties obligate Cameroon to respect and protect the civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights of all its citizens, including those in the Anglophone regions. The ICCPR, for instance, emphasises the importance of respecting the rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and the prohibition of arbitrary detention – areas where Cameroon has faced criticism in its handling of the Anglophone crisis. The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, as well as the African Union’s 1969 Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, set forth obligations for the protection of refugees. Betts (2013) discusses the importance of these conventions in protecting individuals who flee their countries due to conflicts. Additionally, the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, as McAdam (2014) describes, also provide a framework for the protection and assistance of internally displaced persons (IDPs), a significant issue in the Anglophone crisis. Cameroon’s ratification of this convention imposes legal obligations to prevent acts of torture within its territory. Nowak (2008) have emphasised the importance of this convention in holding states accountable for the treatment of persons in custody, an issue of relevance given the allegations of human rights abuses by security forces in the Anglophone crisis. For Henckaerts and Doswald-Beck (2005), IHL sets out the responsibilities of states and non-state actors in the conduct of hostilities, including the protection of civilians and non-combatants. The adherence to these international norms is essential not only for resolving the current crisis but also for ensuring the long-term stability and protection of human rights in the country. The international community, through various mechanisms, has a role in monitoring and ensuring Cameroon’s compliance with these obligations.

Key Recommendations and Strategies for Implementation:

Enhanced Diplomatic Engagement:

– Recommendation:

The United Nations should spearhead a renewed diplomatic initiative to facilitate inclusive dialogue between the Cameroonian government and Anglophone leaders.

– Implementation:

This initiative should involve key regional and international actors, such as the African Union, the Commonwealth, and Francophonie. Zartman (1985) establishes how effective diplomacy requires identifying a ‘ripe moment’ for negotiation, characterised by a mutual recognition of a hurting stalemate. The UN can leverage its influence to create conditions conducive for dialogue, including confidence-building measures and possibly sanctions or incentives.

2. Humanitarian Aid and Support for Refugees and IDPs

– Recommendation:

Scale up humanitarian assistance to affected populations and support neighbouring countries in managing the refugee influx.

– Implementation:

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and international NGOs should coordinate efforts to provide immediate aid, including food, shelter, and medical services. Long-term support, as discussed by Betts (2013) should focus on sustainable solutions like local integration, voluntary repatriation, and resettlement. For IDPs, the UN should advocate for the implementation of the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, ensuring their protection and support for eventual return or resettlement.

3. Monitoring and Accountability Measures:

– Recommendation:

Establish an Independent International Commission to monitor human rights violations and hold perpetrators accountable.

– Implementation:

This commission should be mandated by the UN Human Rights Council and should include experts in international human rights and humanitarian law. Nowak (2008) claims that such bodies play a crucial role in documenting abuses and recommending actions. The commission should collaborate with the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate and prosecute those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Additionally, it should work towards building local capacities for justice and reconciliation.

These recommendations are aimed at addressing the immediate humanitarian crisis and laying the groundwork for a long-term resolution of the conflict. Their successful implementation requires coordinated efforts from various stakeholders, including the UN, regional organisations, national governments, and civil society. Through a combination of diplomatic engagement, humanitarian support, and accountability measures, the international community can contribute significantly to resolving the crisis in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon and restoring peace and stability in the region.

References

Amnesty International. (2017). “Cameroon’s Secret Torture Chambers: Human Rights Violations and War Crimes in the Fight Against Boko Haram”. Available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr17/6536/2017/en/

Accessed on 25/11/23

Amnesty International. (2022). “Report on human rights abuses in Cameroon”. Available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/POL1032022021ENGLISH.pdf

Accessed on 25/11/23

Awasom, N. (2000). The Reunification Question in Cameroon History: Was the Bride an Enthusiastic or Reluctant One?’. Available at

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4187333.pdf

Accessed on 27/11/23

Betts, A. (2013). ‘Survival Migration: Failed Governance and the Crisis of Displacement’’. Cornell University Press. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt32b5cd

Accessed on 11/12/23

Donnelly, J. (2013). ‘Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice’. (NED-New edition, 3). Cornell University Press. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt1xx5q2

Accessed 11/12/23

Fombad, C. M. (1998). ‘The New Cameroonian Constitutional Council in a Comparative Perspective: Progress or Retrogression?’ Journal of African Law, 42(2), 172–186. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/745543 accessed on 11/12/23

Freedom House. (2020). ‘Freedom in the World 2020: Cameroon’. Available at https://freedomhouse.org/country/cameroon/freedom-world/2020 Accessed on 11/12/23

Henckaerts, J.M., & Doswald-Beck, L. (2005). ‘Customary International Humanitarian Law’. Available at https://assets.cambridge.org/97805218/08996/frontmatter/9780521808996_frontmatter.pdf

Accessed on 09/12/23

Herbst, J. (1989). ‘State Politics in Zimbabwe’. Available at

https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/_/TtzuDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PR3

accessed on 11/12/23

Human Rights Watch. (2019). ‘Cameroon: New Abuses by Both Sides’.

Available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/08/02/cameroon-new-abuses-both-sides.

Accessed on 08/12/23

International Crisis Group. (2019). ‘Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis: How to Get to Talks?’. Available at

https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/cameroon/272-crise-anglophone-au-cameroun-comment-arriver-aux-pourparlers

accessed on 07/12/23

Joseph, R. (1977). ‘Radical Nationalism in Cameroun: Social Origins of the UPC Rebellion’. The Clarendon Press, Oxford. Available at

https://www.scholars.northwestern.edu/en/publications/radical-nationalism-in-cameroun-social-origins-of-the-upc-rebelli

Accessed on 07/12/23

Konings, P., & Nyamnjoh, F. B. (1997). ‘The Anglophone Problem in Cameroon’. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 35(2), 207–229. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/161679

Accessed on 05/12/23

McAdam, J. (2011). ‘Climate Change Displacement and International Law: Complementary Protection’. Available at https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/4dff16e99.pdf

Accessed on 03/12/23

Mbembe, A. (2001). ‘On the Postcolony’ (1st ed.). University of California Press. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ppkxs

Accessed on 98/12/23

Norwegian Refugee Council/Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. (2020). ‘Global Report on Internal Displacement’. Available at https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2020/

Accessed on 12/12/23

Nowak, Manfred. (2008). ‘The United Nations Convention Against Torture: A Commentary’.

Nugent, P. (2004). ‘Africa Since Independence’.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2020). [Report on Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria]. Available at

https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/gr2020/pdf/Chapter_WestCentralAfrica.pdf#_ga=2.245473156.1215543118.1702375232-1511919280.1702375231

accessed on 12/12/23

United Nations Office for Central Africa (UNOCA). (2020). [Reports on diplomatic efforts in Cameroon]. Available at

https://unoca.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/20th_report_of_the_un_secretary-general_on_the_situation_in_central_africa_and_on_the_activities_of_unoca.pdf

accessed on 12/12/23

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). (2023). [Report on the humanitarian situation in Cameroon].

United Nations Security Council. (2020). [Secretary-General’s report on the Central African region]. Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N20/315/31/PDF/N2031531.pdf?OpenElement Accessed on 12/12/23

Zartman, I. W. (1985). ‘Ripe for Resolution: Conflict and Intervention in Africa’. (New York: Oxford University Press, for the Council on Foreign Relations) American Political Science Review. Cambridge University Press, doi: 10.2307/1960942.

Leave a comment