Global Security

Brice Nitcheu

The eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been trapped in a complex and lengthy humanitarian crisis for decades. Since the 1990s, this region has been the centre of conflict, involving several armed groups, including the notorious M23 rebels, and serving as a stage for regional proxy wars (UNHCR, 2024). The crisis is fuelled by a toxic combination of factors: competition over vast mineral resources, deep-rooted ethnic tensions, weak governance structures, and persistent foreign interference. As of 2025, the scale of internal displacement in eastern DRC has reached staggering proportions, with over 7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), of which 4.6 million are concentrated in the volatile North and South Kivu provinces alone (IDMC, 2024). This report examines the multifaceted humanitarian crisis, analysing displacement trends, camp conditions, sexual violence, NGO interventions, and systemic failures over the period from 2012 to 2025.

Scale of Internal Displacement

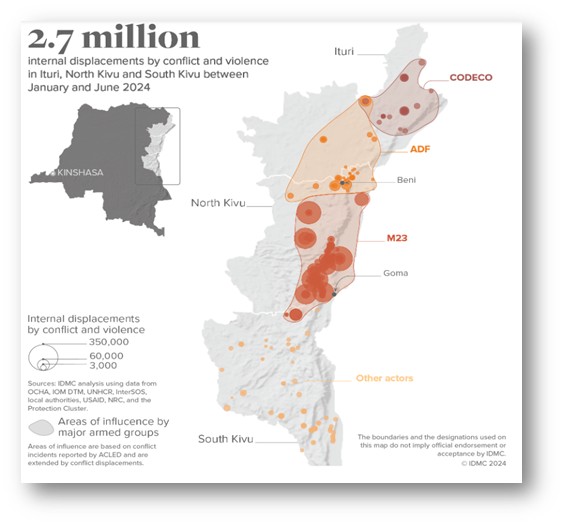

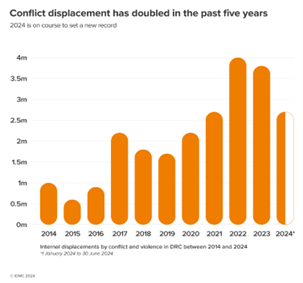

The trajectory of internal displacement in eastern DRC from 2012 to 2025 paints a grim picture of escalating human suffering. In 2012, the number of IDPs stood at 2.7 million. By 2023, this figure had more than doubled to 6.2 million, and as of 2025, it has surged to an unprecedented 7 million (UNHCR, 2024). This dramatic increase can be attributed to several factors, chief among them being the resurgence of the M23 rebel group and intensified intercommunal violence. The period between 2024 and 2025 saw particularly sharp spikes in displacement. In early 2024, renewed clashes in the territories of Masisi and Rutshuru led to the displacement of 738,000 people (NRC, 2025). By mid-2024, this number had escalated to 940,000, with over 480,000 people forced to flee in January 2025 alone (OCHA, 2024). These statistics underscore the volatile nature of the conflict and the rapidity with which largescale displacement can occur in the region.

A key characteristic of displacement in eastern DRC is its prolonged nature, often involving multiple displacements for the same individuals or communities. This phenomenon is exemplified by the situation in Masisi in 2025, where 25,000 IDPs who had previously returned to their homes were forced to flee again due to renewed fighting (Tearfund, 2024). This cycle of displacement and return, only to be displaced again, reflects the persistent insecurity and the failure of so called “durable solutions” in the region. The dynamics of forced migration in eastern DRC are complex, encompassing both conflict induced, and disaster induced displacement. While armed group activities, such as M23 raids, are the primary driver of displacement, natural disasters like volcanic eruptions and floods also contribute to the crisis. This multifaceted nature of displacement complicates humanitarian responses and stretches already limited resources.

Conditions in IDP Camps and Host Communities

The conditions in IDP camps and host communities across eastern DRC are dire, characterized by severe overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and a chronic lack of basic services. Camps near the city of Goma, such as Kanyaruchinya and Mugunga, have become emblematic of the crisis. In 2024 and the first months of 2025, these camps housed between 55,000 and 90,000 IDPs, with woefully inadequate facilities: one toilet for every 1,500 people and one shower for every 3,000 (Oxfam, 2024). The lack of proper sanitation and clean water has led to recurrent health crises. Cholera and mpox outbreaks have become increasingly common, with the DRC recording the highest number of mpox cases globally in 2024 (WHO, 2024).

These outbreaks not only aggravate the suffering of IDPs but also strain the already overwhelmed healthcare system in the region. Perhaps most notably, the camps themselves have become targets for armed groups, compromising the safety of civilians and hindering humanitarian operations. The militarisation of camps has led to tragic incidents, such as the massacre of 12 civilians in Mugunga camp in May 2024 (Human Rights Watch, 2024). This infiltration by armed groups not only poses immediate physical threats to IDPs but also creates an atmosphere of constant fear and insecurity.

Sexual Violence as a Weapon of War

Sexual violence has been weaponized in the eastern DRC conflict to an extent that is both shocking and heartbreaking. The statistics paint a horrifying picture: documented cases of rape rose from 40,000 in 2021 to 113,000 in 2023, with a staggering 79% of these cases involving gang rape (Physicians for Human Rights, 2024). In 2024 alone, Médecins Sans Frontières treated 17,000 survivors of sexual violence across five provinces (MSF, 2024). The brutality of these attacks is difficult to comprehend. Survivors as young as 9 years old have reported genital mutilation using tree branches and knives (Save the Children, 2024). One particularly harrowing account comes from Florence, a 16 year old girl who became pregnant after being raped by M23 fighters (Human Rights Watch, 2023). These are not isolated incidents but part of a systematic campaign of terror.

The impact of this sexual violence extends far beyond the immediate physical trauma. Survivors often face severe medical complications, including fistulas and HIV infection. Moreover, the social stigma attached to sexual violence can lead to ostracisation from families and communities, compounding the survivors’ suffering. Perhaps most disturbingly, there is a pervasive culture of impunity surrounding these crimes. Less than 5% of perpetrators face trial, and even UN peacekeepers have been implicated in abuses (MONUSCO, 2024). This lack of accountability not only denies justice to survivors but also perpetuates the cycle of violence.

NGO Responses and Challenges

In the face of this overwhelming humanitarian crisis, numerous Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) have stepped in to provide critical assistance, often filling gaps left by the absence of state services. However, these organisations face significant challenges in their operations, ranging from security concerns to funding shortages.

NGOs face numerous operational barriers. Between January and November 2024, 217 security incidents involving humanitarian workers were recorded (OCHA, 2024). Some organisations suspended staff movement for two weeks in late October due to insecurity in Ituri province (UNHCR, 2024). Armed robberies of humanitarian organisations have been reported on various routes in South Kivu (OCHA, 2024). Funding shortages persist, with only 50% of the 2024 Humanitarian Response Plan funded as of November 2024 (OCHA, 2024). Bureaucratic hurdles and direct targeting of NGO assets, including offices, health centres, and warehouses, further complicate aid delivery.

Despite these challenges, NGOs are adapting by maintaining presence in insecure areas (MSF, 2024), collaborating with local authorities to strengthen security (UNHCR, 2024), and implementing community-based protection systems (Oxfam, 2024). The humanitarian situation remains critical, with expectations of worsening conditions in 2025. NGOs are calling for increased funding, improved security measures, and enhanced coordination to address the crisis effectively (OCHA, 2024).

As the crisis continues to evolve, the resilience and adaptability of NGOs operating in eastern DRC will be tested. Their ability to navigate the challenging landscape while continuing to provide essential services will be crucial in mitigating the suffering of millions of displaced Congolese and working towards a more stable future for the region.

Conclusion

While the humanitarian crisis in eastern DRC remains one of the most complex and protracted in the world, there are pathways to improvement. By combining immediate humanitarian action with long term strategies addressing root causes, there is hope for alleviating the suffering of millions of displaced Congolese and building a foundation for lasting peace and stability in the region.

Recommendations

– There is an urgent need to bolster ICC prosecutions for sexual violence and impose sanctions on external actors supporting armed groups like M23.

– Integrating IDPs voices into disarmament programs and camp governance can lead to more sustainable and effective interventions.

– Long term solutions must focus on regulating the mineral trade, demobilising armed groups, and investing in local governance structures.

– Improved security measures in and around IDPs camps are crucial to prevent infiltration by armed groups and protect vulnerable populations.

– Given the widespread trauma experienced by IDPs, particularly survivors of sexual violence, there is a critical need for expanded mental health and psychosocial support services.

References

- Human Rights Watch (2023) DR Congo: Killings, Rapes by Rwanda-Backed M23 Rebels. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/06/13/dr-congo-killings-rapes-rwanda-backed-m23-rebels (Accessed: 20 February 25).

- Human Rights Watch (2024) World Report 2024: Democratic Republic of Congo. New York: Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/country-chapters/democratic-republic-congo (Accessed: 10 March 25).

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (2024) M23 Conflict and Displacement in DRC. Available at: https://www.internal-displacement.org/expert-analysis/m23-conflict-caused-nearly-3-out-of-every-4-displacements-in-the-drc-this-year/ (Accessed: 25 February 25).

- Jacobs, C. and Kyamusugulwa, P.M. (2018) ‘Everyday justice for the internally displaced in a context of fragility: The case of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 31(2), pp. 179–196.

- MONUSCO (2024) Report on the Human Rights Situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Kinshasa: United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the DR Congo. Available at: https://monusco.unmissions.org/en/human-rights-reports-and-publications (Accessed: 14 March 25).

- Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) (2024a) DRC: Responding to Sexual Violence in North Kivu. Available at: https://www.msf.org/msf-survey-shows-scale-violence-against-displaced-women-eastern-drc (Accessed: 10 March 25).

- Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) (2024b) MSF has and Continues to Treat More Than Two Victims of Sexual Violence Every Hour in DRC. Available at: https://www.msf.org/msf-has-and-continues-treat-more-two-victims-sexual-violence-hour-drc (Accessed: 12 March 25).

- Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) (2025) Eastern DR Congo: Displacement and Humanitarian Crisis. Available at: https://www.nrc.no/news/2025/february/eastern-dr-congo-hundreds-of-thousands-displaced-in-wave-of-extreme-violence (Accessed: 26 February 25).

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (2024) Global Humanitarian Overview 2025. Available at: https://digitallibrary.in.one.un.org/TempPdfFiles/38871_1.pdf (Accessed: 03 March 25).

- Oxfam (2024) Responding to the Crisis in Eastern DRC. Available at: https://www.oxfam.org/en/what-we-do/emergencies/crisis-democratic-republic-congo (Accessed: 05 March 25).

- Physicians for Human Rights (2024) Conflict-Related Sexual Violence in Eastern DRC. Available at: https://phr.org/our-work/resources/massive-influx-of-cases-sexual-violence-drc/ (Accessed: 10 March 25).

- Save the Children (2024) Children Face Mass Sexual Violence in DRC. Available at: https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/news/media-centre/press-releases/children-face-mass-sexual-violence-and-mutilation-in-the-drc (Accessed: 03 March 25).

- Tearfund (2024) DRC: Where Refugee Camps Are No Longer Safe Refuge. Available at: https://www.tearfund.org/stories/2024/05/drc-where-refugee-camps-are-no-longer-safe-refuge (Accessed: 03 March 25).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2024) Democratic Republic of the Congo Situation Report. Available at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/democratic-republic-congo-situation (Accessed: 25 February 25).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2025a) Democratic Republic of the Congo Situation. Available at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/democratic-republic-congo-situation (Accessed: 14 March 25).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2025b) Escalating Violence in Eastern DR Congo Displaces More Than 230,000 Since Start of Year. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/news/briefing-notes/escalating-violence-eastern-dr-congo-displaces-more-230-000-start-year (Accessed: 14 March 25).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2025c) Response to New Emergencies and Protracted Crises. Available at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2025-01/2024%20Response%20to%20New%20Emergencies%20and%20Ongoing%20Crises%20v3%201.pdf (Accessed: 12 March 25).

- United Nations (2024) Highlight 30 September 2024. Available at: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/highlight/2024-09-30.html (Accessed 08 March 25).

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2024) Mpox Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON522 (Accessed: 10 March 25).

Leave a comment